Growth or decline? The factors behind US international student enrollments

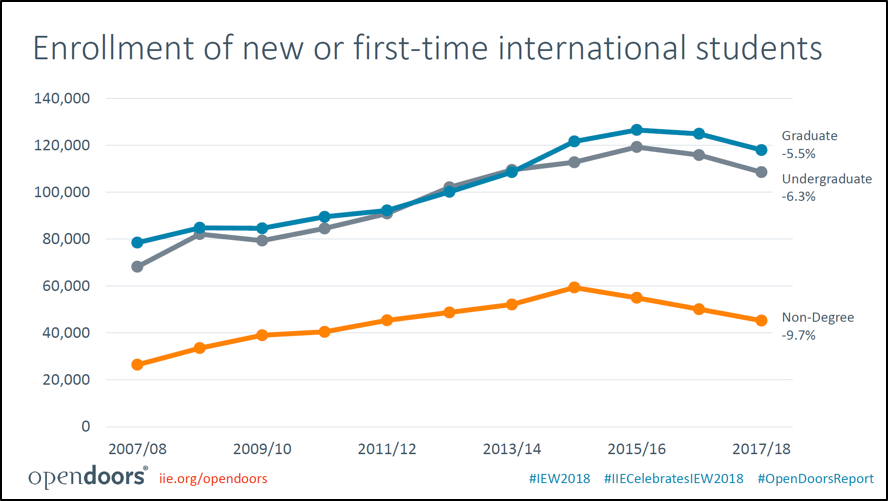

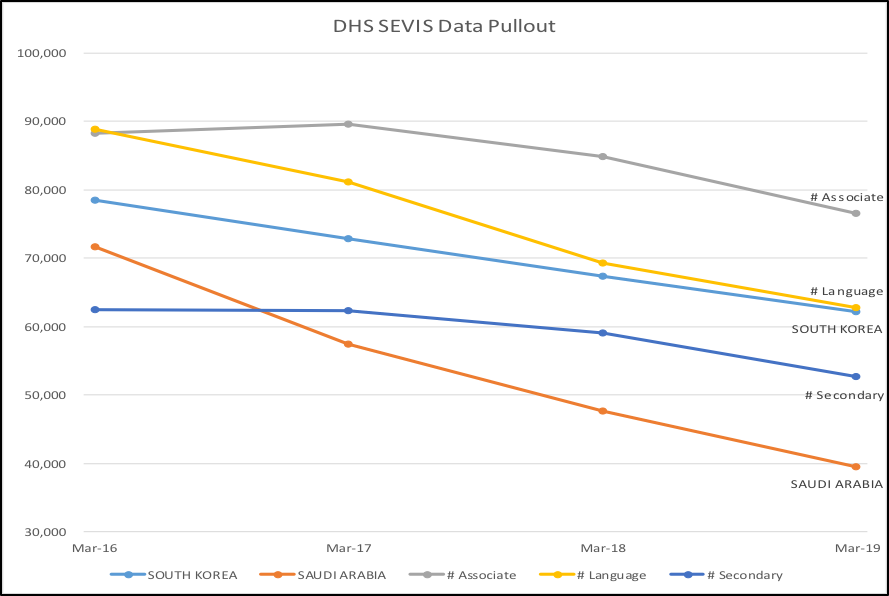

When thinking about global education in the United States these days, it’s easy to point out what’s wrong. IIE Open Doors data shows falling new international student enrollments over the past two years. Three-year declines in the number of Associate, Language, and Secondary international students are definitive, according to SEVIS by the Numbers Data, as are drops in the overall number of Korean and Saudi students.

Experts are quick to point to higher tuition prices, concerns about safety and student visa uncertainty – as well as the rising number of lower-cost, higher-quality alternatives in other countries.

But is this deepening deficit-mindedness warranted? Is the United States destined to stay around one million international students through the 2020s and beyond? For enrollments to grow, institutions, programs and partnerships will need to provide high-quality education with real-world applicability. Will enrollments continue to concentrate at the top (for example, at NYU, USC, Columbia, and Arizona State)? Or will we see international enrollments rise across a multitude of cities and institutions (including community colleges and regional comprehensives) in response to demographic and technological trends? And most crucially, what’s the role of international private-public partnerships in helping shape this future?

I see three distinct possibilities. First, a Business-as-Usual future with modest incremental growth, second, a decline of international student growth, and finally, a robust international enrollment expansion – driven by a renewed sense of partnership potential including joint-advocacy for positive policy developments at both the state and federal level. Let me explain.

Business-As-Usual (BAU) future

In a BAU future, we would see no change in post-study work rights through Optional Practical Training (OPT) or other programs, little progress in restructuring the American immigration system, increased visa rejections, and increased competition from the UK, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere.

International student enrollments would continue to be driven to research-focused and high-ranking national and elite institutions, as well as established major metro areas like New York and Los Angeles. International student growth would continue at around 3% per year, resulting in around 1.3million enrollments by 2030, with flat enrollment across two-year colleges and regional comprehensives.

Unfortunately, the 3% growth rate would not alleviate the overall decline in student enrollment, which will accelerate after 2025 according to Grawe. Some states, like Illinois, Michigan, and New Hampshire, are projected to see 15% contraction across all institution-types through to 2030. The only cities projected to have enrollment gains are Denver, Houston, Charlotte, and Atlanta.

International contraction future

This scenario would see the end of major post-work study rights with the cancellation of OPT, continued uncertainty overseas about the safety and value of study in the US, and much stronger competition from abroad.

Visa rejections would continue to hamper future enrollment from growth markets, and protecting US intellectual property and academic research would be under renewed focus, with restrictions on international student majors or fields of study (including a country cap for student visas).

The result? Potentially three or four years of negative growth to 2024, reducing overall international enrollment to 900,000 students, with longer-term gains bringing the 2030 national enrollment to 950,000 students. These students would be increasingly concentrated in cities with significant immigration populations and at institutions with strong overseas ties.

International expansion future

In this scenario, the United States enacts policies to counteract the above-mentioned student demographic declines – especially through expanded post-study work rights. Following the UK’s example, the US could award two years of post-study work for earning an Associate degree and three-plus years for a bachelor or beyond. Higher numbers of H1-B visas (for occupations requiring a bachelor’s degree or higher) would also encourage students to consider the US.

State-based international recruitment strategies would potentially increase, especially for states with challenging demographics like the Ohio G.R.E.A.T. campaign.

Finally, if the US followed the UK and Australia, international student agency regulation would strengthen the voluntary standards currently set by the American International Recruitment Council (AIRC).

The cumulative effect of these changes would likely increase international growth to a healthy 7.5% per annum, resulting in 2 million enrollments by 2030. While large US metros would still attract a sizable number of these students, numbers would be less concentrated compared with the other two scenarios.

Implications for international private-public partnerships

While it’s clear that the expansion future would be hugely beneficial to our respective partnerships and the industry overall, we must also come to terms with some rather negative industry trends of our own. Over the last two years, international student private-public partnerships have contracted by at least 13 programs, down to 64. Study Group, the Cambridge Education Group, and Kings Education have all reduced their US footprint, while EC and ILSC have simply exited the US altogether.

The rate of new partnership formations in 2019 have significantly decreased as well, with only a few new programs added in 2019 – Navitas-Queens College, Shorelight-Cleveland State, Kaplan-ASU, and INTO-Hofstra University.

Successful collaboration requires a partnership that is both assertive and highly collaborative. It is not easy to create and maintain this approach, but the potential long-term relationship benefits are immense.

The first step towards true collaboration is to move beyond the label ‘pathway provider’ as it doesn’t fully capture all the value private providers bring to university partnerships. This includes direct recruitment of international students, managed overseas campuses, and other international and local student support services.

It is important to note that unlike the UK, Australia, and Canada, the US doesn’t run separate colleges or foundation programs – a point of contrast that is often lost on potential students, agents, and even our own staff. Second, successful private partners must accept external oversight and outcomes-based transparency by independent third parties such as AIRC and other accreditation bodies. Third, given the importance of federal and state policy, our industry together with our respected partners should work together around a common set of policy objectives and shared values.

Finally, given the rise of data-driven decision making, our industry should develop technology-driven prediction capabilities (such as AI) to drive improved recruitment and student success, while safeguarding student data privacy.

While our industry continues to adapt and change, the fundamentals of building strong, long-lasting partnerships have not. Irrespective of the future scenario for international education, there will still be an important role for private providers. However, long-term success and even survival will depend on three capabilities: a stronger strategic alignment with university partners, an unwavering focus on student outcomes, and the ability to adapt to a rapidly changing and unpredictable market.