Transitioning to an education sector of the future

Education is a wonderful sector to work in because, unarguably, education has a positive impact on society. Pretty much everyone benefits from education – economies perform better, and there are higher levels of individual income and wellbeing.

Yet, for the most part, education has not moved with the times. While some things have changed (digital whiteboards, tablets and laptops), our classrooms today look much the same as they did 50 years ago. Processes and structures are also much the same – the nine to three school day, the rigidity of a term structure, one too many teaching models, and rows of desks and chairs.

As a sector we need to evolve to continue to deliver for students, the economy and for broader society. This starts by acknowledging the challenges we face.

First, in a world that has become more sophisticated, more data-driven and increasingly more personalised to individual needs, our education model is an outdated, one-size-fits-all experience. Your phone can send you alerts when you approach somewhere you like to shop and tell you what’s on sale, but a teacher can’t adjust their teaching to the personal needs of a student in the same, customised way.

Second, education has largely been unable to tap the benefits of scale that are readily available in many other industries. Most educational institutions have one or a limited number of campuses – typically defined by geography and designed to maintain a sense of place and belonging to a community.

Third, lack of scalability, together with high levels of regulation and low levels of private sector involvement, have also meant lower rates of productivity growth in education compared with other sectors. The result is the cost of education is increasing relative to other parts of the economy. For example, the ratio of support staff to academic staff in Australian universities is typically higher than organisations in other knowledge-based industries such as professional services firms, and the large asset bases of universities are largely under-utilised.

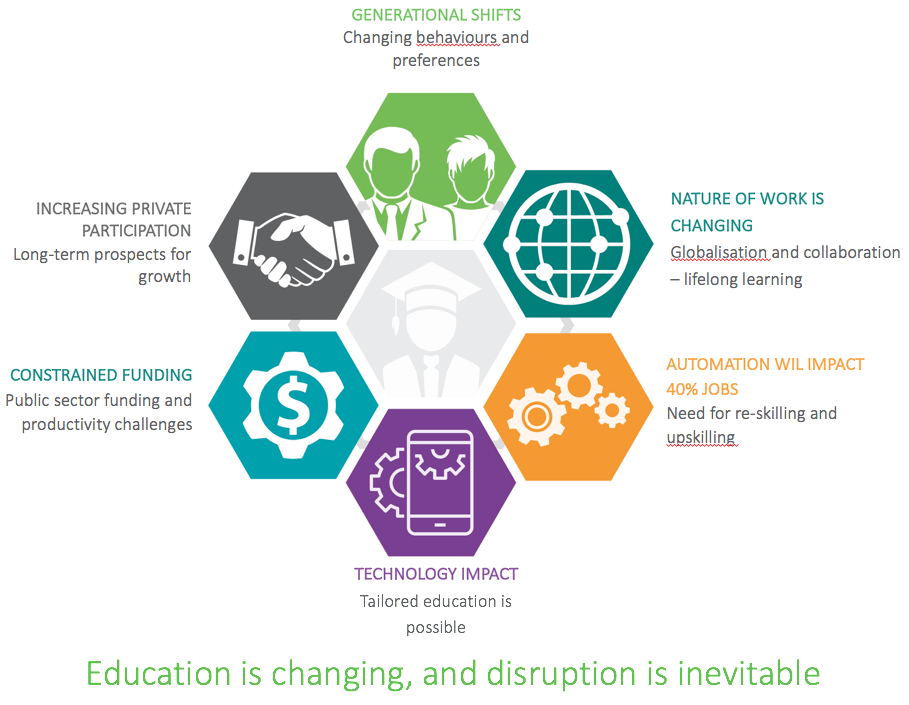

Compounding these challenges are broader trends affecting both supply and demand across the sector. On the demand side, generational shifts will mean future students will want to learn in different ways and changes to the nature of work will make traditional curriculum and modes of learning outdated. On the supply side, new technologies will change delivery methods, and the increasing need to do more with less funding will mean education institutions will need to think differently.

So, how are these factors affecting our traditional models of education and what role will education play in our new world?

Generational shifts

When I started thinking about how the demand for education is changing, I was reminded of my own family story and my own education journey.

Neither of my parents finished school, let alone university. They saw education as a means to a better job for their kids.

They encouraged me to pursue education to the greatest extent possible from an early age and I took their advice – but I was one of only a handful of students in my year at Rockingham Senior High School in Western Australia to attend university. For my generation, education was an aspiration and a privilege.

Today, my own sons are now at university, along with almost all their friends. Their education journey is completely different from mine – they are more focused on the journey and less focused on the destination:

- They’re learning for the sake of learning, to discover their own talents and capabilities

- They’re innately entrepreneurial, committing to multiple paid and voluntary jobs and activities while studying

- They rarely seem to think about a career in the traditional sense of the word – they fully expect to have lots of jobs and several major career shifts throughout their lifetimes

Changes to the nature of work

When I started working as an economist at the Reserve Bank of Australia, I expected to be there for a long time – a career for life. The reality of work today is very different and the result will be a shift towards retraining and lifelong learning.

A good example is the ongoing impact of the ‘gig economy’ – where everyone is an entrepreneur. A recent study predicts that by 2020, 40 per cent of US workers will be independent contractors. How do we teach the next generation to thrive in this new world of work, where relationship building, assessment of risk and 21st century skills – enduring capabilities such as problem solving, financial literacy, digital literacy, teamwork, communication, creativity, critical thinking and presentation skills – are the most critical skills for success?

And how do we ensure that the various parts of the education system – from pre-school to university – work together to build the right foundations for students in these areas of ever-increasing importance?

It’s no wonder a recent survey of our university partners showed Vice Chancellors remain focused on ‘meeting changing student and workforce needs’. In the past, universities were the keepers and distributors of knowledge, and that knowledge was typically taught through mastery of a core discipline. You learned a lot about a narrow range of things.

Today, university courses are beginning to adjust to the changing nature of work through the addition of broadening perspectives, international aspects and real-world projects to the traditional academic rigour involved in the mastery of a core discipline.

The impact of automation on the jobs of today is another illustration of the changing nature of work. More than 40 per cent of jobs in Australia are at risk of being highly affected by computerisation and automation – particularly those that are routine and rules-based. (This is not just for blue-collar roles; it will also affect sectors such as law and medicine.) Globally, tens of millions of people will need reskilling and upskilling.

This is not all bad.

In response to the claim that robots will take all our jobs, economist Milton Friedman noted that: “Human wants and needs are infinite, and so there will always be new industries, there will always be new professions.” Centuries of economic progress confirm this view. Today there are myriad professions no one ever heard of a few decades ago – think social media manager, software engineer, rideshare driver, wellbeing coach, website builder or barista.

The tasks lost to automation are typically the most dangerous, least enjoyable, and the least likely to be associated with high pay. Moving these tasks from people to machines results in fewer work injuries, fewer work errors and higher work satisfaction levels as workers can focus on more creative and interpersonal activities.

Regardless, our education systems will need to shift to help make this transition seamless.

Impact of technology

Traditional education providers already understand it’s a case of ‘disrupt, or be disrupted’ and the disruption in education will be felt at every stage of the student life cycle – from the creation and personalisation of learning content, to finding and applying for courses, to connecting students, teachers and industry, to creating new credentials and to planning careers and finding jobs.

But for the here and now, our own research tells us that students really just want us to get the basics right – they want technology to be reflected in essential elements of their learning environment just as it is in other parts of their life, with easy admission systems and easy online communication with their peers, teachers and employers.

Funding pressures

In Australia and globally, governments are under pressure with high levels of public debt. Schools and universities need to prepare for an environment where any growth in funding will come from non-government sources – students, industry and philanthropists. These are all fiercely competitive.

Institutions will be forced to create new, leaner business models as they are required to do more with less. This is likely to involve more use of digital channels and third-party partnerships for recruiting and teaching students, and outsourcing parts of the back office.

This change is essential. But it will be difficult, given the extent of what is required. In my experience, it is more difficult than achieving the same degree of change in the corporate sector.

In the corporate world, power resides largely with the executive team. In education, the concepts of shared governance, academic freedom and low staff turnover make it challenging to mandate broad change. Education leaders may have a sense of what needs to be done, but they’ll need a focused strategy, organisational support and a sustainable financial base to not only survive but to thrive.

At an institutional level, that means defining areas to invest in, but also, importantly means identifying what NOT to do. And, at a sector level, we need to ensure the focus is on education’s role as a main driver of our economic future to make the business case for governments and companies to invest in that future.

Responding to these trends

To respond to all these trends, it will be increasingly important to bring together industry and education. There is scope for private and corporate sectors to play a much larger role in the education sector. Corporations today invest 16 times more in global health than global education despite similar levels of regulation.

Yet education has extremely strong long-term prospects for growth given the demand trends I have already described. There were two billion middle-class young people in the world in 2016 – many in developing countries and eager for education.

The Navitas model of pathway programs and managed campuses is one model of successful private participation. Increasingly, private equity firms are recognising these investment opportunities. Over the past five years venture capital investment into education companies has been growing at 45 per cent and Facebook, Apple and Google are all showing an interest in the emerging EdTech space. We are also seeing more corporate support of individual universities to support research and development and to develop specific skills.

A view to 2025

This brings me back to the fundamental question I posed at the beginning: what role will education play in our new world? No one has a crystal ball, but analysis of the various disrupting forces I’ve touched on informs our views on likely future directions. Merely tweaking our existing model is unlikely to be enough, but let’s look forward just seven years, to 2025 and some of the trends we might see emerge:

- Universities are adapting all courses to the changing demands from students and from employers and are beginning to focus more on ’21st century skills’

- All areas of tertiary study are offering more personalised education, and the proliferation of online delivery has accelerated

- Government funding has shifted to focus more on outcomes and on reskilling as economies transition globally

- Technology providers have responded to the needs of students and education providers at each stage of the education value chain and we’ll see simplified processes and higher productivity

There is no doubt this kind of transformation will not just happen. The change required to innovate, to embrace technological potential and to work together to meet the ever-changing needs of learners and employers must be envisaged and must be planned and resourced.

This will require difficult decisions and trade-offs between alternative investments as well as new sources of funds. It will depend on collective leadership and vision within governments, schools, universities and businesses. It will require education policy globally that provides certainty, flexibility, simplicity and collaboration like we have never seen before.

Yet the benefits of such a change cannot be undersold. An investment in education today is an investment in our future – and an opportunity to create a lasting legacy by powering our most valuable resource: knowledge.